Raising meat and respecting the environment

By Philip Moscovitch

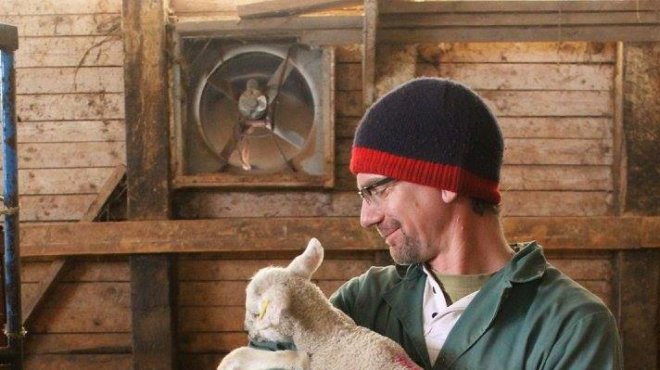

John Duynisveld (MSc’99) is a beef research biologist who practices what he preaches on his farm.

John was born the year his parents moved onto their farm in Wallace, Nova Scotia. Forty-six years later, he runs the place, overseeing cows, sheep, pigs, chickens and turkeys—oh, and a couple of donkeys—grazing on about 300 acres of pasture.

Pasture is something of a passion for Duynisveld, a finalist for the 2016 Nova Scotia Farm Environmental Stewardship Award. In his job as a researcher at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada’s Kentville Research and Development Centre, he focuses on beef forage systems and lessening the environmental impact of raising beef. Meanwhile, on his farm, he practices “adaptive pasture management”—a system that sees animals frequently moving onto fresh grass and minimizes the use of feeds.

“Cows kind of stick their tongue out, wrap it around a bunch of grass, and then tear it off with their bottom teeth, whereas sheep can pick individual leaves and pieces off—and then pigs tend to be harder to predict,” Duynisveld says. By moving these animals around in the fields, the plant life remains healthier. “You’re constantly trying to keep things in that optimal state of growth. And at the same time, that’s providing for each animal to go through and kind of pick what they need for their own nutrition.”

“Cows kind of stick their tongue out, wrap it around a bunch of grass, and then tear it off with their bottom teeth, whereas sheep can pick individual leaves and pieces off—and then pigs tend to be harder to predict,” Duynisveld says. By moving these animals around in the fields, the plant life remains healthier. “You’re constantly trying to keep things in that optimal state of growth. And at the same time, that’s providing for each animal to go through and kind of pick what they need for their own nutrition.”

“We get the animals to eat as much pasture as possible. They’re healthier, the food they produce is healthier for us, and it’s good for the environment.”

And there’s another benefit too: storing carbon. “If you manage a perennial system well, it can result in a net gain in the amount of carbon that’s stored in the soil,” Duynisveld says.

At Ag Canada, Duynisveld is working on a five-year project with a team from Quebec, studying carbon in the soil to a depth of 60 cm. “We’re looking at the profile of the amount of carbon in the soil at different depths—it’s broken into different layers. That’s never been studied in Eastern Canada on a foraged system,” he says.

Duynisveld has taught at the Dalhousie Faculty of Agriculture in the past, continues to supervise a graduate student and has had several students study his farm for their honours theses. Some of their work has looked at how little grain pastured chickens consume. That doesn’t just lower costs for the farmer, it also has benefits for consumers. “Grasses have a fundamentally different nutritional profile which is transferred into the meat of the animals,” Duynisveld says. “Animals raised on green grasses are higher in Omega 3 fats and lower in Omega 6 fats. The more grass an animal eats, the more its nutritional profile actually gets to be more like that of fish.”

Both of Duynisveld’s children grew up helping on the farm, and now his daughter Maria looks set to follow his career path. He says, “My daughter is interested in carrying on with the farm. She worked with me the last couple of summers and now she’s off to the Dal AC.”