Barry Johns (BArch’72): Architect of change

By Mark Campbell

It was the summer of ’67 and young people from across North America were converging in San Francisco with flowers in their hair and notions of changing the world. Barry Johns (BArch (NSTC)’72) had similar notions, but they came to him in his hometown of Montreal while exploring the architecture along the fairgrounds of Expo ’67.

It was the summer of ’67 and young people from across North America were converging in San Francisco with flowers in their hair and notions of changing the world. Barry Johns (BArch (NSTC)’72) had similar notions, but they came to him in his hometown of Montreal while exploring the architecture along the fairgrounds of Expo ’67.

“I couldn’t get enough of it,” says Johns. “To see designs like Moshe Safdie’s Habitat ’67 gave me this fantastic sense of optimism that the built environment could enhance the quality of our lives. I knew then I wanted to be part of a profession that could do that.”

Life-changing architecture

Nearly 50 years have passed and it’s clear this Governor General Award-winning Dalhousie alumnus has lost none of the passion for architecture he discovered that fateful summer, or its power to effect change. If anything, it appears to have deepened with each project on his extensive and impressive resume. From his days with Arthur Erickson as part of the team that created Vancouver’s iconic Robson Square to the many acclaimed educational, community and recreational facilities he’s designed through his own Edmonton, Alberta-based practice, Johns has devoted himself to work that stimulates the same optimism that Expo ’67 inspired in him. “Good architecture,” he observes, “transforms lives for the better.”

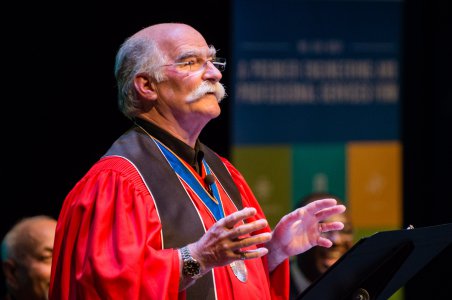

So do good architects like Johns. He’s been a proponent of sustainable design for 30 years, predating the existence of LEED certification in Canada. He believes in the making of places that are authentic to their location by respecting the local characteristics of site, culture and climate. He’s advocated on behalf of his profession, most recently in his second term as Chancellor of the College of Fellows of the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada. He’s encouraged design that contributes to a greater sense of community through initiatives such as the Edmonton Design Review Panel, which he co- founded in the 1980s and chaired. And he’s encouraging a new generation to do transformative work through teaching and lectures at colleges and universities across North America. Much to his delight, that includes his alma mater, Dalhousie.

So do good architects like Johns. He’s been a proponent of sustainable design for 30 years, predating the existence of LEED certification in Canada. He believes in the making of places that are authentic to their location by respecting the local characteristics of site, culture and climate. He’s advocated on behalf of his profession, most recently in his second term as Chancellor of the College of Fellows of the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada. He’s encouraged design that contributes to a greater sense of community through initiatives such as the Edmonton Design Review Panel, which he co- founded in the 1980s and chaired. And he’s encouraging a new generation to do transformative work through teaching and lectures at colleges and universities across North America. Much to his delight, that includes his alma mater, Dalhousie.

Recruiting Dal talent

“It’s a real thrill because Dalhousie attracts the best students,” says Johns, who has also established a design scholarship and, with his wife, Margo, a family bursary to support Dalhousie architect students who both excel and are in need of financial assistance.

“That (attracting the best students) says a lot about the university’s reputation, and I think it continues to take the learning experience to the next level. I try to get back as often as I can.”

Part of the reason for those return trips, Johns admits, is to find co-op and graduate talent to work in his studio. “We’ve constantly had students from Dalhousie among our staff since I started my own practice. I’m very proud to say we’ve spawned at least four or five good young practices in Alberta and BC, and as many partners in other firms.”

For Johns, teaching is more than an opportunity to recruit bright young minds or impart his considerable knowledge and experience. It’s a way to recharge his batteries and reconnect with his youthful idealism. “You get to observe the intelligence of young people, exchange ideas around matters that have a huge impact on architecture and explore new ways of thinking about the profession. You learn as much from your students as they learn from you.”

Early inspiration and paying it forward

It is also a way for Johns to give back, to inspire students to follow their passion just as people in his life encouraged him to follow his. There was the uncle who gave him a copy of Frank Lloyd Wright’s The Living City. A high school gym teacher who also worked as a draftsman referred Johns to a Montreal architectural firm for a summer job. And a student he met there encouraged him to head east to the former Nova Scotia Technical School to earn his degree. But it was the professors he met at NSTC , specifically Anthony Jackson and Peter Jacobs, who would most influence his philosophy and career path.

“Jackson was a theorist, historian and critic. He challenged students all the time, teaching us to think. And Jacobs showed me the connection between landscape and architecture, and how design could treat ecology in harmony. I’m forever in their debt.”

You can certainly see their influence on Johns’ work, which has consistently challenged conventional design, advanced the principles of sustainability and, perhaps most important, transformed communities and lives. “The projects that we do must have a redeeming value, and if they do not, then I’m not interested. Our history in practice has been completely backboned by those principles.”

Career highlights

With that kind of focus, it’s hard to pick one project that is representative of Johns’ philosophy, but his work on the Grant McEwan Community College (now MacEwan University) holds a special place. Completed in 1993, the linked yet distinct buildings of this urban campus not only reconnected city districts previously bisected by a railway, they served as a magnet for investment and renewal of Edmonton’s warehouse district. Such is the impact of the college on the community that, in 2014, more than 20 years after it was completed, it won an Edmonton Urban Design Award in the newly launched People’s Choice category.

With that kind of focus, it’s hard to pick one project that is representative of Johns’ philosophy, but his work on the Grant McEwan Community College (now MacEwan University) holds a special place. Completed in 1993, the linked yet distinct buildings of this urban campus not only reconnected city districts previously bisected by a railway, they served as a magnet for investment and renewal of Edmonton’s warehouse district. Such is the impact of the college on the community that, in 2014, more than 20 years after it was completed, it won an Edmonton Urban Design Award in the newly launched People’s Choice category.

“Usually when you win an award, and to date we have about 85, it’s largely due to the judgment of your peers. But, for the public to declare they love your work, that’s a much bigger deal. To know that you transformed enough lives to make it count and created something people love, you couldn’t ask for more.”

But if Johns had to pick a highlight of his career, it could be the Moriyama RAIC International Prize, which he developed in partnership with Toronto architect Raymond Moriyama. ‘Ray wanted to inaugurate it as a way to give back, so I helped him with it. It’s given to an architect from anywhere in the world who submits a project that is juried to be exemplary in terms of social justice, equality and environmental responsibility. We awarded the first prize last year to a young architect from Beijing who designed a small community library in a Chinese mountain village that is completely off the electrical and infrastructure grid. It’s a beautiful and transformative project and it’s helped put this village on the map.”

But if Johns had to pick a highlight of his career, it could be the Moriyama RAIC International Prize, which he developed in partnership with Toronto architect Raymond Moriyama. ‘Ray wanted to inaugurate it as a way to give back, so I helped him with it. It’s given to an architect from anywhere in the world who submits a project that is juried to be exemplary in terms of social justice, equality and environmental responsibility. We awarded the first prize last year to a young architect from Beijing who designed a small community library in a Chinese mountain village that is completely off the electrical and infrastructure grid. It’s a beautiful and transformative project and it’s helped put this village on the map.”

Calling on his profession to step up

For all that Johns has accomplished, there is still more he wants to do. He has set his sights on regeneration – designing a public building that would produce more energy than it consumes. It’s an idea that came to him while collaborating on the award-winning Blatchford redevelopment plan, which would convert the former Edmonton municipal airport site into a carbon-neutral community for 25,000 people.

“I’ve always believed in treading lightly on the earth,” says Johns. “Buildings account for 50% of all energy used through their construction and lifecycle. There’s a litany of criteria we can use to make buildings a lot more efficient, from energy smart appliances to proper envelope construction and renewable energy.”

More than that, Johns would like to see his profession step up its efforts to save and beautify the built environment. Through his role as an educator, advocate and creator of transformative work, he hopes to further advance that philosophy.

“I believe it’s time we claim our place as stewards of this planet that is so fragile. We need holistic thinking and architects to champion doing the right thing when it comes to the making of public policy, buildings and cities. It is an exciting time for the next generation as a result, so practice and education remain a commitment for me.”

To learn more about Barry Johns’ works, see Dalhousie Architectural Press’ publication Barry Johns Architects (2000).